At the Science Mill, we love dinosaurs—we’re guessing you do, too! But in this blog, we want to show some love to pterosaurs: prehistoric flying reptiles that lived among dinosaurs, but were NOT dinosaurs.

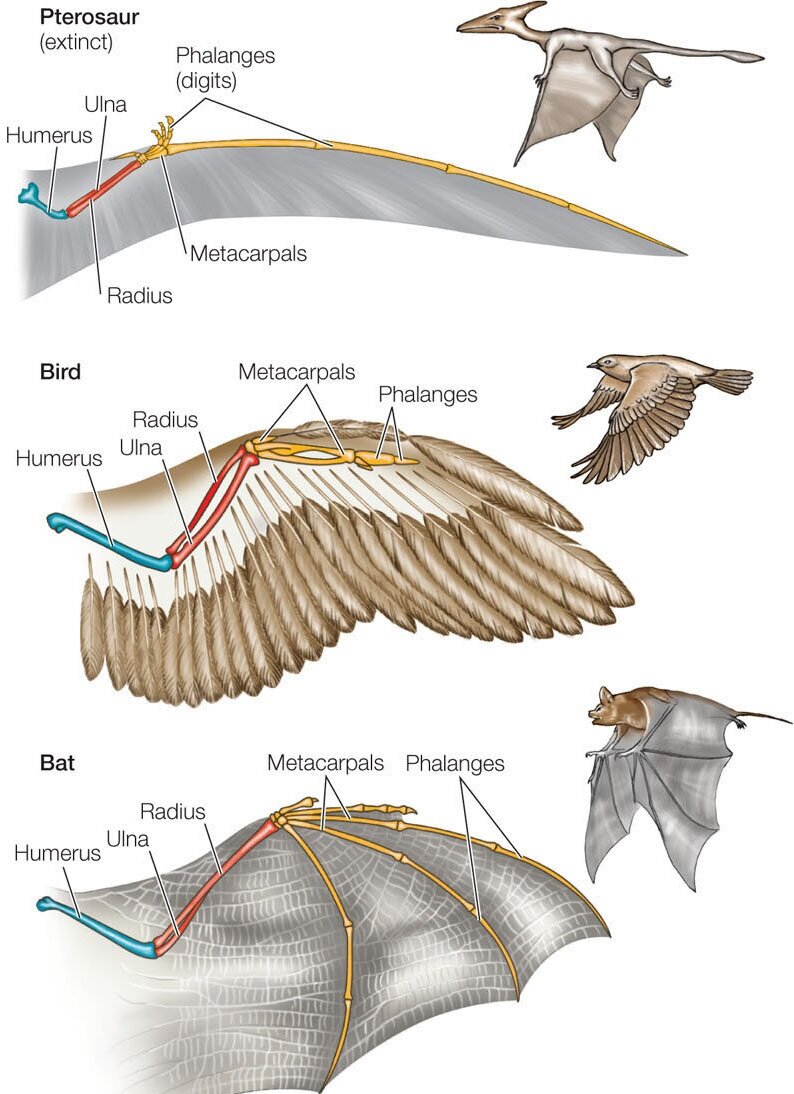

In case you missed Part 1, pterosaurs ranged in size from sparrows to Cessna airplanes and had wild adaptations, including big heads, crazy crests and special membrane wings supported by super-long 4th fingers. What’s not to love?!

If dinosaurs ruled the Earth, pterosaurs definitely ruled the skies. But how they flew is a mystery paleontologists are still piecing together. You can try flying as a pterosaur in Jurassic Flight 4D, the Science Mill’s new 4D virtual reality experience! To celebrate its opening, join us Saturday, May 29 for Jurassic Experience, a day of dino-themed activities and special screenings of Flying Monsters, which features some of the paleontologists in this blog.

(artist: Chase Stone)

How did pterosaurs fly?

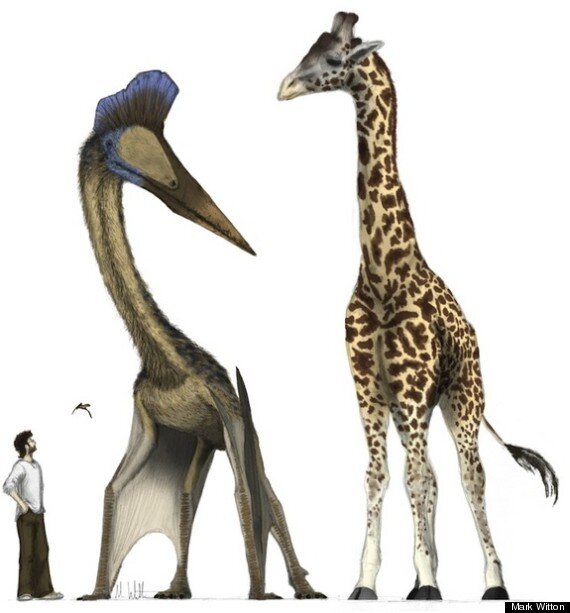

This is one of the big debates about pterosaurs: were all of them really able to fly—even the giraffe-sized species? This is where mathematics and computer models come in.

One computer simulation, developed by paleontologist Sankar Chatterjee and his team at Texas Tech University, suggests that an animal the size of a fighter jet would need a runway. “It probably had to find a sloping area like a riverbank,” explains Dr. Chatterjee, “then run quickly on four feet, then two, to pick up enough power to get into the air.” Once in the air, it was a graceful if frightening sight. “This animal probably flew like an albatross or a frigate bird in that it could soar and glide very well.”

Paleontologist Michael B. Habib and others have a different theory, based on computer simulations of pterosaurs’ launch power—no runway needed. “Flying animals do not flap their way into the air,” notes Dr. Habib. Instead, takeoff starts with a powerful jump, and four-limbed pterosaurs had double the power. “The legs would have pushed first, followed by the arms, for a perfect one-two push-off.” Some have compared the move to pole-vaulting.

(credit: Julia Molnar, via Scientific American)

But what about those enormous heads? If pterosaurs flew with their wings angled forward, as calculations by Dr. Colin Palmer and his team suggest, their big heads would be balanced. New fossils offer additional clues. CT scans of a pterosaur vertebrae recently revealed a strength-building secret: a “tube within a tube” structure supported by spokes, similar to a bicycle wheel. Paleontologist Cariad Williams and her team calculate that for a pterosaur with a 4-foot neck, adding just 50 spokes to its vertebrae would allow it to lift 90% more weight—roughly equal to picking up prey that weighed 24 pounds.

Are there pterosaurs living today?

No—pterosaurs went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period. While birds evolved from dinosaurs, pterosaurs have no living descendants. They do, however, have mechanical relatives!

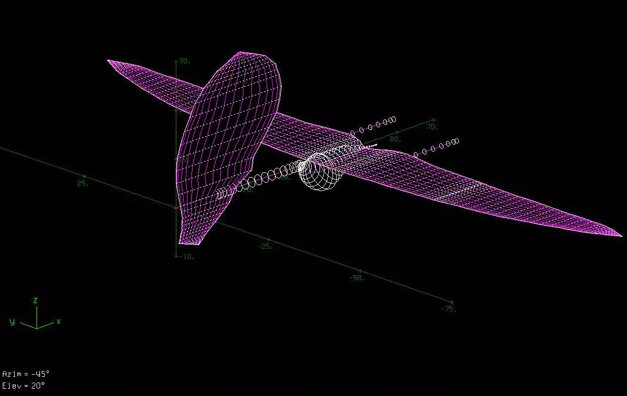

Experimental designs for Pterodrone (images: Brian Roberts)

Dr. Chatterjee and Rick Lind, an aeronautical engineer, teamed up to create a drone inspired by pterosaurs’ unique flying adaptations. Named “Pterodrone,” the drone’s design includes membrane-inspired morphing wings and an adjustable crest in the front. The features make the drone a more versatile flier in tight spaces. In the future, they hope to add the pterosaurs’ ability to walk and possibly sail.

TRY IT AT HOME OR SCHOOL

Animal Design Challenge

Research on pterosaurs helped Dr. Chatterjee and Dr. Lind design a new drone. Their work used biomimicry: an approach to technological innovation that draws ideas from nature. To experiment with biomimicry, try this Animal Design Challenge alone, with a partner or with a group!

Supplies

Slips of paper, index cards or Post-its (enough for each participant to get two)

Pencils or pens for writing

Colored pencils, crayons or markers for drawing

Dr. Chatterjee with a skeleton reconstruction of the pterosaur that inspired the Pterodrone’s design. (credit: AP Photo/Artie Ummer)

On half the cards, write an animal—one per card. (Prehistoric animals are fair game!)

On the other half of the cards, write a short everyday problem—one per card. (EX: Keep construction workers safe; chop up vegetables; carry a heavy bag)

Mix up the animal cards and have each person take one; mix up the problem cards and have each person take one of those, too.

Brainstorm! How could your animal inspire a solution to your problem? Maybe something about their body? How they move, or where they live? Jot down your ideas.

Design! Pick one of your ideas and sketch out a prototype for a new product or system. Try to show how it would work.

If you’re working solo, pick another animal card and see if you can add on to your prototype; or pick another problem card, too, and start again!

If you’re working with a partner or group, share your ideas. After seeing everyone’s animals, problems and prototypes, what new combinations do you see for biomimicry inspiration?

Keep observing and brainstorming! Study plants and animals outside, a pet at home—who knows where your next big idea might come from?

CAREER CONNECTION

“An aircraft based on pterosaur concepts may be able to fly to a rooftop then walk under an overhang to mount a sensor in a dark corner.” — paleontologist Sankar Chatterjee and aeronautical engineers Rick Lind and Brian Roberts, on their inspiration for Pterdrone

MORE TO EXPLORE

Explorer Zone Episode 4: Masters of Disguise

Labs on the Go: Bug Inspired Biomimicry (Grades 6-8)

Check out our new Labs on the Go series for Grades K-8: Each Lab combines hands-on STEM activities with video “field trips” that show science in action. Everything you need ships directly to your classroom and is supported through an easy-to-navigate online learning system!

Become a citizen scientist!

Join people across the country who gather data to support scientific research. Pollinator projects include monarch counts, milkweed mapping, bee surveys and more, which you can do in your backyard and local community. The Xerces Society has a list of butterfly and bee projects around the country. Also check out the “Projects” section of iNaturalist, available online and as a mobile app, for projects on birds, frogs, trees and more.

CAREER CONNECTION:

“Don’t be afraid to experiment! In any garden, you will find that some plants are more successful than others—embrace the victories, but remember the defeats. The garden is a journey, not a destination.” — Kirk Alston, horticultural specialist